Summary

Antibodies have a major role in protection against infection.

SPAD is considered as a diagnosis in individuals with a history of recurrent upper and lower respiratory infections, but normal total levels of immunoglobulins and no major findings in other components of the immune system. SPAD is a mild type of primary immunodeficiency where those affected do not produce sufficient antibodies to protect the body from certain bacteria. Symptoms of SPAD include an increased occurrence of upper and lower respiratory infections. SPAD can affect both sexes and people of all ages. Treatments include prompt treatment of infections with antibiotics, use of antibiotics to prevent infection and very rarely the use of immunoglobulin replacement therapy. With appropriate treatment the outlook for people with SPAD is generally good and most people live normal, healthy lives.

What is specific antibody deficiency (SPAD)?

Antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins, play a vital role in the immune system and keeping us healthy. Antibodies help the immune system fight infections and can prevent infections coming back in the future, but at certain ages this protection does not always work so well. Specific antibody deficiency can be thought of as a more extreme form of this normal impairment to protection against certain infective agents that is seen in infancy and older life.

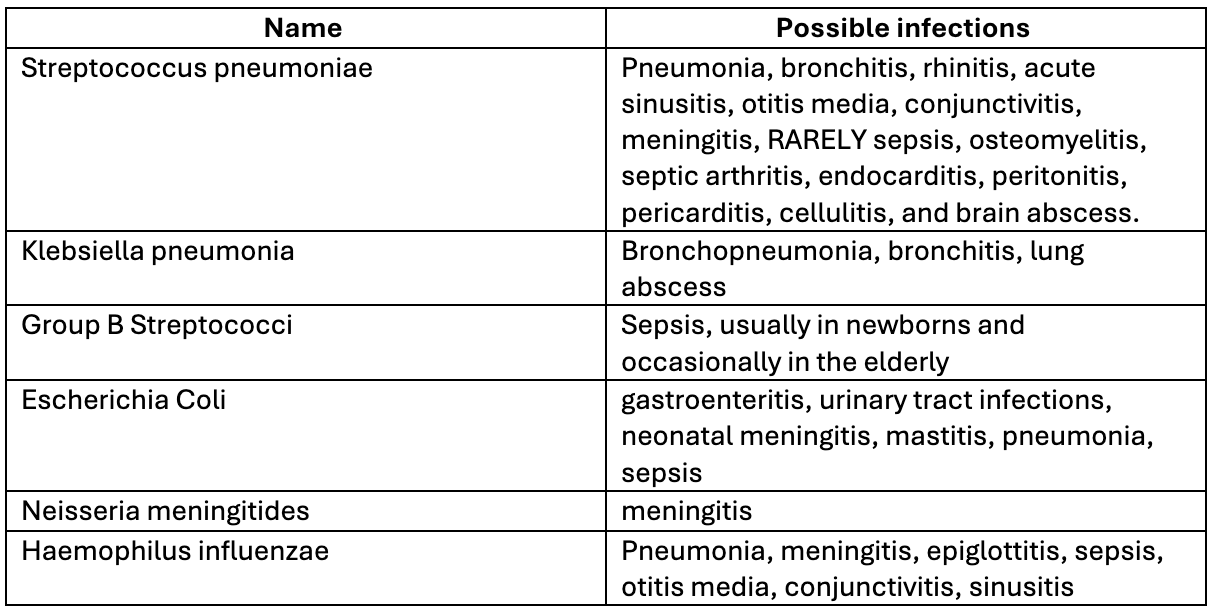

In people with SPAD the ability to make good quality antibodies to certain bacteria never develops properly. The diagnosis was originally restricted to the failure to make a response to a specific type of encapsulated bacteria (bacteria that are coated with sugars known as polysaccharides) called pneumococcus (streptococcus pneumoniae), but many immunologists now make the diagnosis when the total levels of antibody production in a patient are normal, but there is an absent or poor response to any encapsulated bacteria (Table 1). Although, there are a range of microbes that cause infection, doctors will not test for responses to all of them. The basis of a diagnosis of SPAD will be made on the response to a vaccine.

Table 1. Types of encapsulated bacteria and possible infections caused.

SPAD is a condition that affects males and females, all age groups and can vary in its severity. It is not possible to diagnose this early in life because children are not expected to respond to encapsulated bacteria for their first few years (see below). SPAD can sometimes be referred to as selective antibody deficiency, partial antibody deficiency and impaired polysaccharide responsiveness.

Encapsulated bacteria, conjugate vaccines and immune responses

Encapsulated bacteria, such as streptococcus pneumoniae or pneumococcus can cause pneumonia and meningitis, with babies and older people at particular risk. Young children with developing immune systems are unable to make responses against pneumococcus and similar bacteria reliably for the first few years of life because the sugary coat of the bacteria makes it difficult for the immune system to respond. Babies are therefore at risk of invasive disease from these types of bacteria because they cannot eradicate them quickly. Because of this, protection is included in the childhood vaccination schedule through the vaccine Prevanar™, (other vaccines are used in some parts of the world e.g. Apexxnar™ or Vaxneuvance™), that does not rely on a polysaccharide response.

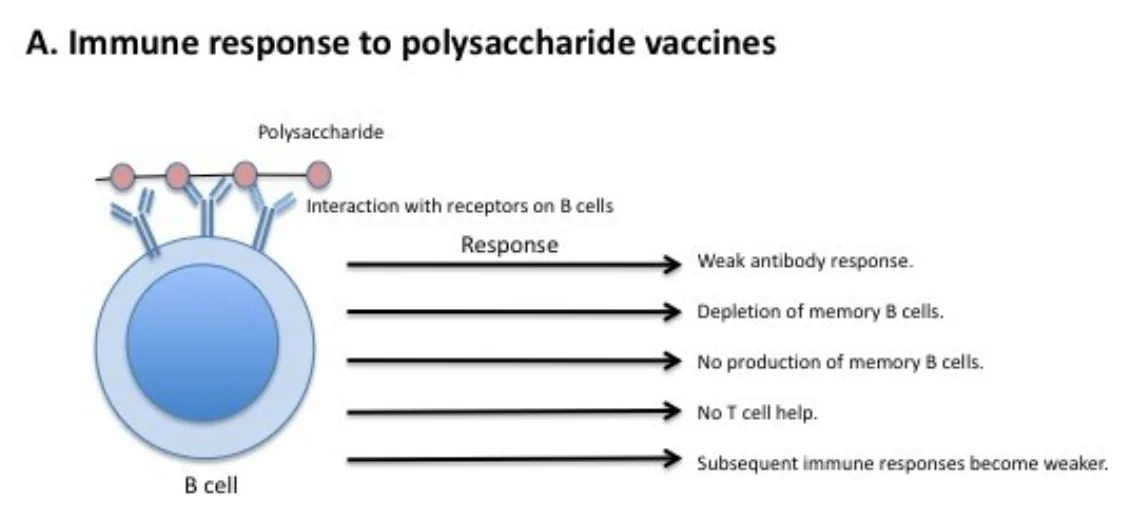

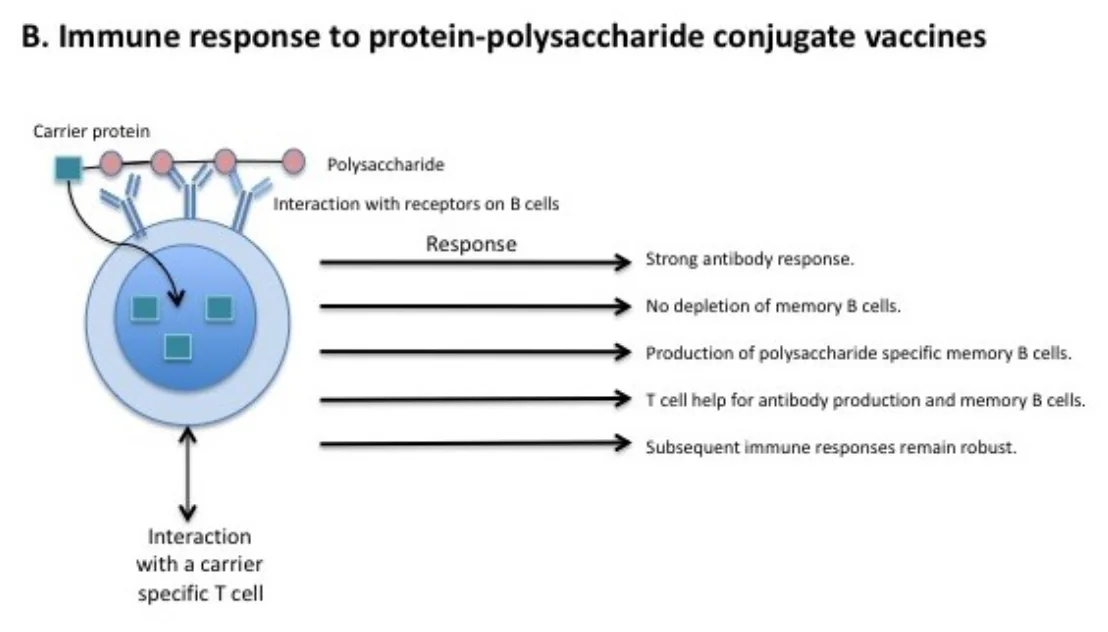

Our immune system is designed to make antibodies to proteins and not sugars so to help children with developing immune systems make protective antibodies to encapsulated bacteria, vaccines have been developed that integrate a way of tricking the immune system to respond. This is done by linking the sugars from the coating of the bacteria to a carrier protein e.g. parts of diphtheria or tetanus protein. This allows antibodies in children previously vaccinated against diphtheria or tetanus to respond and helps amplify the immune response (Figure 1). Vaccines that have this protein-sugar (polysaccharide) structure are called conjugated vaccines.

In older life when the immune system wanes infections caused by pneumococcus can become a problem again and so older people are vaccinated with the whole inactivated bacteria (Pneumovax™) to help give them protection against developing pneumonia. There are plans to change the adult vaccine to Prevanar because the protection offered is often more robust.

Pneumovax™ is also used throughout life as a booster vaccination for people at risk from more severe invasive infection such as people with immune deficiency or asthma.

Figure 1. The immune response to polysaccharide and protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccines

A. Polysaccharides from the encapsulated bacteria that cause disease in early childhood stimulate B cells and drive the production of antibodies (immunoglobulins). This process results in the lack of production of new memory B cells and a depletion of the B cell memory cell pool, such that subsequent immune responses are decreased. B. The carrier protein from protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccines is processed by polysaccharide-specific B cell and presented to a carrier specific T cell. This results in T cell help for the production of antibody producing B cells and memory B cells.

Adapted from Pollard, A., Perrett, K. & Beverley, P. Maintaining protection against invasive bacteria with protein–polysaccharide conjugate vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol 9, 213–220 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2494

How did I get SPAD?

There are three major classes or kinds of immunoglobulin, and each has a slightly different function in preventing microorganisms from successfully invading body tissues and causing serious infections.

- Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is the most abundant and common immunoglobulin, found in blood and tissue fluids. IgG functions mainly against bacteria and some viruses.

- Immunoglobulin A (IgA) is found in nasal fluids, bile, tears, sweat and saliva. It protects the tissues of the respiratory (lungs), reproductive, urinary and digestive systems.

- Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is a rapid response antibody and is the first type of protective antibody produced in response to infection.

A type of immune cell known as B cells is responsible for the production of antibodies. In the immune system there is normally constant communication between B cells and other immune cells. The purpose of this communication is to ensure that B cells make antibodies against the correct targets. B cells should make antibodies against infections to help your immune system fight them off. Why some people develop SPAD is the subject of ongoing research, and the causes are not fully understood. One theory is that a problem with the communication between B cells and other cells leads to SPAD.